tv U.S. Senate CSPAN January 7, 2013 8:30am-12:00pm EST

8:30 am

in countries like iraq, like afghanistan. and we ask ourselves were we the good guys? did we get it right? did we do the right thing, or did we do more harm than good? in our questioning, though, i would like us not to look back, not to rehash the past, but let's, if we can, look forward and really reflect on the lessons learned in these interventions and see how they can inform the actions of our community of democracies as we move forward into the future. first, again, we have a panel of luminaries that virtually need no introduction, but i will briefly introduce them nonetheless. first, juan carlos pinson, minister of national defense for colombia, welcome. senator john mccain of arizona, someone who i personally have had the honor to interview back in washington since he was a congressman from

8:31 am

the early '80s. welcome, senator. and our wonderful host, pete mackay. and finally, josef joffe. senator, i would like to start with you. the first panel yesterday was looking at this question of a new normal, and the united states' current light footprint strategy. i could literally feel you chomping at the bit as one of the panelists discussed what he saw as the u.s. role in the world being in such a state of flux now. but we are less willing than ever before to step up to try to solve the chaos in the world, especially when there's no pressing national interest. >> first of all, i think we have to as politicians understand what our constituents, what our citizens, what their priorities are and what their concerns are. our former chairman of the joint chiefs of staff made a comment that's been b often quoted, he

8:32 am

said our greatest national security threat is our economy. and i think that that is absolutely true. when we have half the homes in my state of arizona still underwater, worth less than the mortgages that they're paying, people, obviously, their attention is on that aspect of their lives. and so when we talk about foreign adventures, they're very reluctant particularly with our iraq and afghanistan experiences, they are extremely reluctant. it calls for leadership, it calls for leaders to inform people why it's important what's happening in the arab world, why the rise of radical islam extremism over time poses a threat to us, why china in their sometimes-immature behavior can pose a threat over time to stability in the asia pacific region. so it's up, it's up to us to try

8:33 am

to explain to our citizens and our constituents why it is that we have to do a lot of things. foreign aid, that's the favorite target. i just want to mention one thing. there has always been an element particularly in the republican party, there's always been a conflict. it's between the isolationists and those who believe that were, have a role to play in the world. you could trace it back to after world war i when we rejected united states membership in the league of nations. the prior to world war ii isolationists, lindbergh, ford, all of those. the post-world war ii, and we are seeing that coming back strongly in my party today. >> how much does that concern you, sir? >> concerns me a great deal. we had a vote in the senate by the senator from kentucky just before we went out to cut off aid to pakistan, libya and

8:34 am

egypt. it only got ten votes, but now that's spread all around the far right, uh-oh, they should have voted to cut off that aid. and so we are seeing that emerge in our party and in our or nation, and a lot of people say why should we be spending money on these foreign adventures and foreign assistance when we have so much trouble at home? and that debate will rage now between now and the next elections and, particularly, the next presidential elections. >> minister mackay, your nation has been such a loyal ally to the united states, following us into afghanistan. your country was involved to a lesser extent, certainly, in iraq. but considering the outcome in these two places, how would you say your nation's point of view has changed, if it has, on the

8:35 am

responsibilities of we democracies to take actions like that? >> well, i'll come directly to that, but i want to play off something that senator mccain said. that in considering interventions, military contributions, foreign aid, there's no question that the very stormy economic situation that we've all come through, the pa jillty of the economy -- fragility of the economy still directly influences a government's thought process. it certainly is a determining factor as to what and if a country will contribute to an intervention. >> cutbacks to the british -- >> 25%. i mean, they're tying up ships, there's soldiers in the field getting notices that there won't be a job for them when they return from service overseas. so my father had an expression i thought that was very apt. he said when water in the drinking hole starts to go down, the animals look at each other differently. [laughter]

8:36 am

and -- >> what does that mean as we go forward? >> the water table is low. >> [inaudible] >> so canada joined the united states and others, our allies, in the decision to go to afghanistan. we had a security council resolution. there was a clear indication that had we not, afghanistan would remain an incubator and an exporter of terrorism. so, you know, to answer directly was it the right decision to go, yes. afghanistan certainly no longer poses that threat to the world, and minister wardak who's joining us here i know will have some very insightful comments. but the reality is to bring it into the topic of panel, there is a higher calling, in my view, and an obligation on democracies, on countries that see themselves as, yes, accountable to their

8:37 am

populations -- >> no matter the cost? >> but accountable to the broader world. and we can't sit in splendid isolationing in north america or anywhere else and think the world won't come to our door. it did on 9/11. so not at any cost, not without very informed decision making. often instructed by the security council and other bodies, other consultations, nato being very high on that list. and, you know, what i suspect we'll get to in this panel is syria. what's happening in israel as we gather here this weekend. and so these are the questions of our time. these are the challenges of our generation. and that's, i think, one of the great benefits of opportunities like halifax, to have a very in-depth discussion about how we

8:38 am

act as a community; a community of democracies, a community of countries that care, that are compassionate and that are able to do something to stop the slaughter of innocent civilians. >> of the many who say that we need to as we have more young, emerging democracies like your own that they need to be stepping up to the plate and taking more of the responsibilities. so we're talking indonesia, india, brazil, turkey, south africa. but at the same time, i also hear the statement made and as they get involved increasingly and should step up to the plate and helping to nurture democracy protect human rights, that those countries also have to be careful to make sure their own house is in order in that respect, that those in glass houses can't throw stones. what are your thoughts on that? >> well, i think certainly more nations now have a role to play, and definitely in our case we're trying to play that role based

8:39 am

on our experience. as you maybe might know, most of you, our country just 10, 20 years ago was mentioned always by terrible case of violence, terrible case of terrorism, drug trafficking. that was the main story in our case. i think one important message that i believe for this panel is that certainly democracy is very important. but it is very important when it is the people that really wants to save their own nation and want to play everything around. i think that's a little bit what happened in colombia. in our case certainly very strong, important leadership vision from many of our leaders, but at the same time a national will to recover the country, to find a road, i think, has been critical. and by having that, then you

8:40 am

find international support and cooperation. and i think the case of colombia becomes an interesting case of how international support, but following behind national leadership, can become a proxy that can provide some important results. at the end what we are getting right now is strong institutions, and those institutions are the ones that are luing us to think -- are allowing us to think about a better future, a better democracy. currently, what is going on in our case is that still we have very big challenges, and we know that. but we need to keep doing what we're doing, keep moving forward. and more importantly, we have learned that with a very humble attitude we can offer other nations what we learn, our

8:41 am

experience. and this is what we're trying to do now, to be very humble and at the same time to tell which is what we did, this is what we learn. if you think it is useful, come with us. we can give you these ideas. >> thank you. mr. joffe, as we look at the current economic situation globally today in the united states, obviously, in europe and around the world and we talk about trying to nurture and support democracies and protect human rights, does -- as both the senator and the minister mentioned earlier, does the question morph into, you know, not so much what are what we want to do and what our responsibilities are, but what we can do, what we can afford to do in these days and times? >> well, you're right that we shouldn't dwell too much on the past, but the past of humanitarian intervention or nonintervention teaches us something about the future.

8:42 am

there are five cases. there's -- [inaudible] , there's darfur -- [inaudible] , there's libya and there's now syria. we only intervened in one of them, libya. because when we bombed serbia, that was four years after -- [inaudible] and then if you look at that lineup, some very nasty questions appear when we talk about -- [inaudible] and there are so many of them that had to write them down. first, what moral duty, what moral duty demands how much sacrifice? second, will i have to commit more bloodshed than the bloodshed i want to prevent? three, do i have the capabilities? that's what we're talking about here. what are my chances of success? , four. five, how sustainable is my mission? how much stamina do i have, and that's very relevant if you look at iraq and afghanistan. six is an end to this

8:43 am

intervention. do i have an exit strategy? and seven and finally, what will happen when i leave? will the killing resume? must i come back? now, if you look at it this way and you apply that roster to the five cases, you understand why we intervene in only one case. it was quick, didn't take any sacrifice on our part, we fought from the air. thank god we've got the ammunition from the united states. there was some strategic interest in the part of the europeans. it was coo close to home -- too close to home. and we didn't go on the ground, and we didn't stay. so in other words, and that's where i end, there are some harsh limiting conditions to humanitarian -- [inaudible] and the moral obligation is just one part of the calculus. >> mr. mackay. >> well, i hi it's a very interesting point about the obligation, the burden that we're talking about, and not all

8:44 am

democrats are created equally. not all democracies came about in the same way, the same form or fashion. so one of the subjects around the nato tables annually is burden sharing. um, this leads into this question of what can you contribute? you can contribute something, and can when the decision is made to make an intervention -- which is a very, very difficult one and has, you're absolutely right to suggest there are long-term implications -- you certainly don't want to leave things worse than you found them. and this is, of course, much of the consternation and the stress, i suspect, of people in afghanistan feeling post-2014. what is going to be left behind? will the peace and stability hold? what about the ongoing development projects that are in that country? and that has been true going

8:45 am

back to second world war and beyond. so put it into the context of syria. who can make the most meaningful contributions now? and the contribution doesn't have to be military. russia, i would suggest, should be called upon to step up and belly up to the u.n. security council and exert influence. they, i suggest, are the most influential at this time. and have the ability, number one, to stop supporting this regime that is slaughtering its citizens, to stop by its acquiescence standing on the sidelines and letting it happen while the rest of the world wrings its hands and sucks its teeth. >> how do we accomplish that? >> well, pause i think they can -- because i think they can exert influence in the capital

8:46 am

of syria. i think they're oneover the few countries that really can at this point. iran? forget about it. >> i asked how, how do we get them? >> well, because they could support security council resolutions which thus far we have not been able to achieve because of the reticence of china and russia. >> let's discuss the responsibility. >> go ahead. >> what is the rationale for doing so or not doing so? i think it's got to be based on one principle. ..

8:47 am

how could we have intervened effectively in rwanda? so the strong caveat to that is that we can't right every wrong. we can put at every fire. we can't intervene, even though there's a compelling humanitarian interest, but where we can we should. because it is in our interest to see countries develop, to have a chance for democracy and freedom, and they are things that we've all stood for, certainly in our country, for well over 200 years. so the decision has to be made by policymakers where our interests and our values, but also where it's possible, but also you have to have the support of the american people.

8:48 am

otherwise like the vietnam war, you leave in disarray because the american people lost confidence in their government and in the nation they were on. i still, as good as relations we have with vietnam now, we still condemned a few million people to refugee camps, i mean to the education camps and execution and all of those things. so i think the discussion that has to be made between leaders and their constituents is that if we see something that we can rectify, we should. but we have to understand the limitations of those interventions, because you are far worse off if you fail if you have never gone there to start with. this brings us to syria. i'm ashamed. i'm ashamed. i'm ashamed as an american. i've been to refugee camps and met the women have been gang

8:49 am

raped. i've met the families have watched their kids shot before their eyes. i've met the defectors who said their instructions are to go around and kill and rape and torture. and while we sit by and watch that happen, without even giving them weapons to defend themselves, this will be a shameful chapter in american history, my friends, because we could've done something. and we can do something today but we won't. i hear that the new president has been reelected, we will be re-examining all. only 37,000 people have been massacred, i guess in the grand scheme of things that's not too many compared to some wars, but we could've done something about it, and we can still do something about it, and we can do it collectively and to allow come in all due respect, peter, because russia vetoes the resolution and the security council is the reason for not doing so, to me it was not sufficient reason to not to act.

8:50 am

>> our values are interesting but i'm not sure it's always the case. our interests, the interest was in the case of iraq to maintain that bastion of power against -- [inaudible] then we intervened against the bad guy which required our values, and what we ended up was liberating the power of iran and making iran that much stronger, which is giving us -- let me finish. speed let me say quickly. the perception at the time, the greater threat was the weapons of mass destruction. that was a greater threat, whether right or wrong, we believed that's what the threat from iran was. >> but i'm saying that's one of the outcomes. maybe we could have predicted the outcome. it's a sad outcome where our interest and our values were not

8:51 am

the same. now, we get to syria. the problem with these countries is that there's a civil war there. and in a civil war you don't necessarily do by the bad guys and good guys. so we give weapons to one party, which then makes it and subjugates the other and there's -- the alawites, the kurds, the christians, the few jews who are left. so that is what bothers me so much. in a way we have to be there and stay there, and then protect our former enemies against our former friends who are now beginning to slaughter these guys. so that's why the point is very simple. if you go in you have to be ready to stay and protect those whom you have, when you help the others, we have to protect them. i think we can't just go in and

8:52 am

leave. >> i'd like to bring in -- >> i come from a place where you have a different perspective. listening to this kind of wonderful, to see how, you know, larger nations can think about, but i would, you know, comment on the following. i think certainly when you see human rights violations, when you see the cases senator mccain has described, i understand the moral obligation to step in and find a way to solve things. but i think we are in an era of not intervention but cooperati cooperation. i think, i believe our case could be one to look around. because when you intervene, my impression is that sooner or later you will harm the people

8:53 am

you're trying to support. just by the idea of someone from the outside is trying to solve problems or to take over your own responsibilities. but when you think that you can support a system that is really willing to make things happen, respecting culture, respecting realities, understanding what is behind, i think the potential of that cooperation, that support could bring something more lasting, if i can use the word. so i think it's not a matter of defending, protecting human rights, protecting people, protecting the right values of democracy and respecting human rights, but it's the way.

8:54 am

and i think that kind of discussion should come to these the following years. certainly from my perspective from what we have learned, you have learned in your presence in the middle east, but certainly in other cases like ours in which, i have to tell very openly, if we can see that we have progress, we have not finished but we have progress, our president is on having the vision of peace because what we have done, this friend we have gained, but that has come very well connected with the u.s. support. i have to be very frank. with that kind of cooperation, with that kind of help, and we are nation, the uk has support very much to israel we have asked for the support. i have recently been asking now the minister of canada to support us on some structural reforms. in my case right now, the military reform.

8:55 am

so we have kind of change that kind of support that is allowing us to get into different layers in different levels. not all things are equal, but you have to discuss, depending on what you find. but i would promote more than the intervention. i think that it's better thinking on cooperation, even with difficult partners. >> i'd really love to get to the audience now because we have a fabulous spam and i know you all want your time. scotty. >> thank you so much, scotty greenwood from the united stat states. i just had to quickly thank you, minister mackay, for your convenient hospitality again this year, a brilliant event. and i have to say, thank you to senator mccain for your service to our country and your unvarnished candor as usual. so now to my question.

8:56 am

the good guys, this time, you really are the good guys. and the special burden, i wanted to ask about something else, which is for the first time since you've been convening this all affects group, minister, canada is in the chair of the arctic council. after canada it will be the united states chairmanship. so there are only eight nations that make up the arctic council. the whole world is really interested. china is certainly interested in the maritime commerce potential come in the resources. the potential for environmental catastrophe is pretty gigantic there as well. rescue missions, et cetera. what is the special burden of canada and the united states with respect to the arctic council? should countries like china be allowed on server status, and just briefly while ago, kathleen, kathleen, senator mccain in the last panel, the law of the secrets was mention. you think the next congress will ratify it?

8:57 am

if not, why not? thanks. >> the special burden, the role i think of arctic council members, all of whom are democracies, one of the underpinnings of democracies is a rules-based system is respect for the rule of law. in addition to accountability to the people who elect you. so canada has, you know, tremendous attachment obsession sovereignty over our to believe the largest part of the arctic. and so there are certainly special obligations that come with that. the stewardship of the environment. we have enormous interest of course in our own resources, our people. in fact, 40% of canada's landmass is above the 60th parallel, yet we all have roughly 100,000 of our 34 million people living there. so it is an enormous challenge,

8:58 am

obligation, even to continue to exert the sovereignty, search and rescue. at this time of year is becoming dark 24 hours a day. you have temperatures to plummet below 50 degrees celsius. and you have opening waters and changes that are going to create a lot of challenges because more people simply are going to go there, and more countries have exerted or expressed an interest. you mentioned china. there are many others that want to be part of this council. to your question about the obligation, i think it comes back to people playing by the rules and respecting the fact that there are places when disputes arise, as is the case with canada and the united states impact on the bering sea. some of the bordering areas of

8:59 am

the arctic. i think there is a recognition that countries that adhere to a rule of a rules-based approach, you can go and resolve these in a court come in international court, the u.n. the problem is, and this i think comes back to this whole panel discussion, is that if countries are not democracies they don't respect rules. terrorists don't play by any roles, including ieds and the ground to blow up schoolchildren are putting suicide bombs on mentally disabled people and sending them into a crowded market place. i mean, these are unthinkable atrocities that terrorists commit because they have now, there is no grounding. there is no inhibitions, because not only are they not democracies, they don't add year to any rules whatsoever. and that's what i think some countries -- don't adhere to any rules. some jurors. some jurists have commented that democracies are sometimes

9:00 am

problems were handcuffed in their ability to respond in conflict, as it should be. there should be rules but we are living in a world now where those rules, for many, certainly nonstate actors asafa don't exist, thus the conundrum, how do you respond. and sometimes respond with three straight when your emotions is to do otherwise. >> senator mccain? >> i think we can, john kerry has been very active in this issue. i think it's going to require presidential push to convince a few. and i think it's important step we move forward with that. just one additional -- as i mentioned, we all know, the world is so rapidly changing. the unpredictability of the world is the one thing that a think we would all agree on. and look at the world, as i mentioned last night, the first time we can danger, and look at

9:01 am

it today. so what's it going to be like four years from now? we don't know. we have no real idea because anybody who predicted the world for years ago would likely to say i'd like to meet you. so it seems to me it's even more important to have a common principles of behavior of international behavior. we've got to stick to those principles because if we can't predict -- all of us at least during the cold war live in a very predictable world to we really did. we knew the decisions and we knew what the capabilities were. we don't know what's going to happen. i don't know what's going to happen in china. i don't believe that 1.3 billion people are going to be satisfied for ever under the present regime in which they live. so it seems to me it's even more important that we have certain principles guiding us. and i want to emphasize again, it doesn't mean we go everywhere and fight every battle, pullout

9:02 am

our pistol at every provocation. because it has to be tempered by reality and it has to be tempered by the fact we are democracies and we have to have our people behind us. i've forgotten who the great philosopher was who said show me where my people are going so i can get out in front and lead them. [inaudible] >> you know, i think it was voltaire. and i'm not sure, but it probably -- maybe both. >> i neglected to follow my duties as a moderate but if you would please stand and give us your name and your organization you represent, and then ask a question, thank you. >> i'm from canada. my question is when it comes to the subtitle, but the discussion is a special burden of native

9:03 am

countries and those countries closely outlined like australia, canada, colombia. there are other great democracies that don't see themselves as part of that, africa, brazil. while i would expect those countries to necessarily send troops to libya or something like that, you would expect a greater concern for democracy, human rights, especially in places like zimbabwe or burma. you haven't seen those countries step up and take a leadership role even diplomatically. i think they see themselves not so much as leaders of the democratic world, which they are in the form more leaders of developing or emerging colonies. [inaudible] the democratic values that we share. is there a way we can encourage those companies to play a greater role and see results more as a part of the democratic

9:04 am

powers and sharing common democratic values and putting that as a higher priority in their own policy? >> the short answer would be yes. i think, you know, all of those countries that you listed, and more, certainly in terms of their economic capacity compared to some of the smaller democracies, particularly some in the americas, some that have a long history of embracing democratic values, but wouldn't have the bankroll, if you will, to participate in international mission either militarily or on the development site. again, i keep using afghanistan as a touchstone, but they are some 40 countries have troops on the ground, boots on the ground. but there are 60 plus that are contributing on the development side. japan, sweden, some of those democracies that are really making remarkable difference in

9:05 am

the day-to-day lives of afghans. so there are many ways in which democracies can help spread democracy, which i think is a worthwhile endeavor, that we would agree. and you know there's different ways in which you can engage nonmilitarily that arguably are going to have a much needed affect in parts of the world right now. in some of these troubled areas though, clearly where a tipping point would development is not the issue. spent someone has to protect those and others who dig the wells and teach the kids against the bad guys, right? and as you look around, very interesting question, why aren't other democracies doing the same thing? and apparently, it seems to be anglo-saxon habits. no wonder these are the oldest democracies. u.s. and britain. and the bricks were already --

9:06 am

brits were fighting hard among themselves in 1820s come she would go and help the greeks in the uprising against the turks. >> they sent the scots to do it. [laughter] >> that by the way is a very profound to joke. because if you're an empire that wants to make sure the world lives by some rules or your rules, it's always good to have an imperial cloud so you don't make it in london because you would be discriminate against. and, therefore, go off to build an empire. so an imperial classes are imported. so it just came to me when the question was raised, if you look at the rest of the world, -- germans, the spaniards, you name them, they are not exactly gung ho on putting their blood on the line. when it comes to pursuing and guaranteeing our values.

9:07 am

so the point i guess here is, you've always got to have somebody who runs the show. there has to be one very large power, usually it has an anglo-american, anglo-saxon authority. and we are now in a page, and this is where i will end, of american development where the power that has carried the burden for the last 60 years now as we all know, once to lead from behind, from afghanistan, from iraq. and now exerts its power from afar and from above. drones. and so i feel it nobody picks up the responsibility of organizing and maintaining the policy, it ain't going to be anybody else. there won't be india.

9:08 am

>> go ahead, minister. >> i was just going to comment, i think there's more, threats going on in the world that are allowing nations, democracies, to find each other. speaking about the national crime in general terms come so national crime is really creating a problem for nation states in a sense that we have borders. we have constraints, and certainly we can just not go after all the problems we are finding from drug trafficking to counterfeiting, explosives and weapons, et cetera, et cetera. and i think that allows an opportunity for increasing cooperation. and by the way, those nations that get isolated with some lack of international support equally

9:09 am

confined their system at democracy of risk. in our case, what we're trying is to understand anything that happens to our neighbors, even if they are afar, at the end can become a problem for us. so what i think we are trying to use an approach, not tell them you should do this or you should do that, but going there and asking what do you need? from what i know, tell me what i can do for you. and this is the way i think -- >> a form of intervention. >> right. >> interesting. senator mikulski? >> barbara mikulski from the united states. minister bueno, my question, comments go to you. much of the talk here about what can we do to help these

9:10 am

democracies, has centered around the topic or concept of massively action where military is leaving, and then massive expansion, expenditure of foreign aid. senator mccain rightly says that the people in the united states of america are war weary. but this then goes to colombia, the countries of latin america. so my question is, that if one thinks about other forms where democracy plays a role, education, the empowerment of women, the bringing of science and technology. you're a world bank guy. you went to harvard and did a special the insight technology. so here we are, this tremendous knowledge in these fields. well, we talk about how they democracies, how do you see that

9:11 am

from not only education, at full ride scholarships? that's ours but there are others whether it's french, canadians, the brits. so there are other ways for education, the empowerment of women and racial status inclusion, the international or american bar society helping with institutions. what do you think about that? or is it such that unless you're big much to that unless you big muscular defense, big muscular foreign aid, og, america is trying to toy with income and so is the west. i don't think america will ever be when be in anything, but i'm more of an additional school of thought. what do you think? >> thank you spent what would help colombia and help colombia in what would have latin america? >> thank you. certainly i can tell that the u.s. support and to speak very

9:12 am

frankly on what you have request, the u.s. support on law enforcement in colombia definitely has been healthy. i think that's step one. but as you said, you need several points to develop. so certainly increasing security capabilities, increasing the states ability to promote and protect human rights. in a case like ours where we have so many problems for so many years, what's critical, decisive, and we will continue and need to continue to strengthen those capabilities. but the more that prime minister of defense, i can tell you -- [inaudible] the more i go to far and away places, i get into a jungle or go to the mountains where we are currently under defensive operations to precisely try to bring back these parts of the country, into

9:13 am

a better future. more and more people in those town hall meetings have 10, 15% of the time requesting for security specific issues from my office. but 80% of the time, 85% of the time they asked me for a road, for a health care solution, for an education solution. i think people certainly is right. i think what we are trying, and our experience shows, that no doubt you need to bring security and order to start to have the opportunity of promoting human rights, to promote the right values of democracy and state. but behind that there are many things you have to do in order

9:14 am

to bring a quality come in order to promote opportunities for the people. and i think that's an effort in our case that we have to maybe for the next 20 to 30 years, not just a matter of defeating some drug traffickers or gorillas in one place, but what of it going to bring to this places an order not to allow that to fall in other criminal hands. spent can i just say very quickly, i believe one of the most important aspects of our success in the world is these students who come to the united states and our scholarship programs. i also think our military to military relations -- >> i've got one of those. spent our military to military programs where military from countries all over the world come to the united states to our various if it schools and colleges, and it has paid

9:15 am

incredible dividends. these exchange programs and scholarship, 25,000 chinese students graduate from an american university last year. i believe they go home and they have a tremendous impact and all of it is beneficial. >> i would totally agree, and i think senator mikulski's point is spot on. you know, in order for the developments and the age to take root there has to be the ground prepared. so security is the essential ingredient. it all happens under the amount of security first. i think my colleague from colombia would agree. it's like sowing seeds on a paved parking lot. they're going to blow over. they're not going to take root and leisure the security ground prepared to but education is absolutely key to all of that and enabling women. we are seeing more women sitting in the parliament of afghanistan and in many of our democratic countries. we saw firsthand the impact that girls going to school in that --

9:16 am

that to me would be the absolutely critical piece for that country. if it's to continue to evolve in a positive direction is that women become decision makers. and the enthusiasm with which, i mean, entire generation of young afghan women have embraced education is, it's awe-inspiring as a transformative that will be. but it has to be protected because, to your point, people will get off the back of a helicopter or the plane and they will be slaughtered in less there are soldiers there to protect them, to do their good work. >> next question. >> i'm one of the more like a scots in the british colony. [laughter] >> indeed you are. >> going back to the title of this session, good guys, in the cold war we didn't believe we were different from the so. we believed we were better. we believe in what we stood for and our values were better than theirs. are we in danger now of slipping

9:17 am

into almost a doctrine of the moral equivalence of states, not wanting to talk about our values in case we undermines cooperation in particular i think about human rights in china, women's rights in islamic states. in the future, do we want to still be better or just different? >> if i could attack that first very briefly. i think we may, history shows us that alliances with people who are unsavory, who have oppressed their people, who have engaged in bad and corrupt governments usually turns out not very well, even if it seems to be most convenient at the time. there was an editorial in the "washington post" this morning that i agree with. and that is -- [laughter] spent this is very unusual. [laughter] it shows that even a blind hog

9:18 am

-- anyway. i'm not so sure that the president of the united states should dignify cambodia. is corrupt. these oppressive. and i also do not believe that perhaps it may be time for the president to go to burma. burma has a long way to go. our case for that is on concert she. she didn't think this was the right time to do it. and you bestow presidential visit on the country that doesn't like that country. so i think that we have to be very careful who we ally ourselves with, even if it seems the most expedient at the moment. spent i think you have to action your values. i mean, it's easy to say of course and what does that really mean. but offering encouragement to fledgling democracies, --

9:19 am

[inaudible]. and embracing every single step that countries that are trying to embrace the values that we hold dear. and that means when you think about what is happening to israel. 5000 rockets fired into the country since 9/11. what country on the planet could tolerate that, and going back to the senators opening comments about accountability to the people that elect you. the number one job of any government elected anywhere in the world is to protect the safety and security of its population. and that's why we have militaries, very capable once. you know, i remember -- unsorted our members very recently meeting with some veterans. some who would landed -- which didn't go welcome in some who

9:20 am

would landed at normandy which went better, incessantly. and one of them made a comment about the fact that it seems to be a lot of storm clouds gathering again and war in places seemed imminent. and he said i thought we said never again? well, that was 70 years ago. it's still never again and there are a lot of places that do need protection in the world today. john, you were one that did, that did protect people by your actions. so as scotty has said, we are very grateful for what you have done as a leader. >> i want to make a point. i'm also, we all read in the papers today, and what we suddenly have become aware of is the fundamental transformation of the strategic map of the middle east. all the bad guys were our guys are gone, like mubarak.

9:21 am

probably, probably assad is also a goner. such a nice plate -- place like tunisia has gone islamic. qatar, one of the greatest dependence of the united states is turning towards the extremists. hamas attack on israel is not out of the blue. it comes out of that strategic, change strategic map. so here we are being reminded once more, the careful what you wish for. we want a democracy. we seem to be getting islamization, and thus to the middle east movement that is not, say, friendly towards the west let alone towards israel. so what do we do until the good guys really become good guys, and to islamists become good liberal democrats? and didn't we at the very harsh harsh question i'm asking,

9:22 am

didn't we do better with the mubarak's for the last 40 years? >> let me just responds very quickly which some of us -- summons us back to 2002001, 2002 to try to insert in our foreign aid to egypt, money for economic development in the for human rights, for other reforms that we felt were very necessary because obviously the nature of the mubarak government. and i'm not saying that we should shun every government because they aren't democratic. but what we should do is, through as much persuasive powers as we have, including foreign aid, is to move them in the direction that we seek him to go. but i'd also add that there was nothing in the world that any of us were going to do to prevent the overthrow of mubarak. he was going to go.

9:23 am

and to cling to him after it was very aware that the people of egypt were speaking in a very loud voice, then we were not i think correct in continuing to cling to him. and i do believe that mubarak paid a very heavy price for the lack of the progress. a lot of us saw needed a change in egypt. now, we didn't predict this cataclysmic event, but we certainly predicted that things would get a lot worse in egypt and less he changed and showed progress. i'd like to see the cambodian leader show progress. it's been in the opposite direction. so, i'm not saying this is easy. i'm saying it's very hard. we have people who spend their whole lives trying to solve these things. but i still believe that they've got to be based on some principles from which to act. and i certainly don't think we're always right. >> next question.

9:24 am

>> i fear this reason conversation made my question somewhat redundant but if our values are our interests and our interests are upheld, i think maybe send a mccain could perhaps articulate more clearly what the values under grading -- the u.s. support for rather progressive regime. [inaudible] and it's very easy, but i guess my larger question is, do good guys, do the good guys deserve to be pragmatic? >> first of all, i guess maybe i could make myself very clear. personal in the case of bahrain, i have met with the crown prince but i've met with many others to we have urged him in no uncertain terms to try, that they must make progress there.

9:25 am

and, unfortunately, this may be turning into a shia sunni conflict as much as anything else. i guess i didn't make myself clear. we tried to bring about change where it's possible to bring about change. and we act in -- in fact that doesn't mean that in my view that we tell, draw a line between every country. but we do, our state department every year issues a report about countries that are democratic, nondemocratic and a lot of our actions in the congress are dictated by that assessment and our own. so look i'm a i guess i'm trying to say without, and it's easy i guess to say well, it's right and wrong. but i still don't see anything wrong with the principle of our interests, our values. but accommodate to the practicalities and realities that you are dealing with. i didn't -- when we -- a lot of

9:26 am

us said we've got to make progress in egypt didn't advocate the overthrow of mubarak, but we certainly didn't advocate the reduction in aid and earmarking aid for other reasons rather than military at the time. so you have to handle each one of these situations with a certain amount of pragmatism and a certain amount of recognition that you cannot right every wrong. but what you can do is advocate, and i believe one of the things i am most proud of about the united states, with all our failing at all our flaws and all the mistakes we've made, we are still in the model that most people in the world would like to emulate. and i'm very proud of that. >> we have a question up here. >> thank you. i used to be with the center for european reform in london, now with the new center european

9:27 am

policy in czechoslovakia. if we had this debate five years ago it would've been very different. we would been talking a lot more about enlarging the stability in europe itself by enlarging our institution, the eu or nato. what's happened to that agenda? is a no longer a part of the democratic countries? and if the answer is was so care about -- are whether georgia can become more stable, how do we get smarter about it? it isn't obvious our institutions hold the same if you used to hold five or six years ago. it isn't obvious that comes like ukraine had to stay democratizing instinct, the country of central europe had 10 years ago. so what, if anything, would you do different to make sure part of your democratic in state? >> i'd like to say quickly, i think some countries have taken a bit of an appetite suppressant when he came to their ambitions of being part of the european union, for example.

9:28 am

>> but they are democratic. >> but they are democratic. but there also has to be benefit that flows. i think that is very much a part of the typos as to whether people are going to pursue being part of a larger union, being part of an obsession like nato. there has to be some apparent benefit in so doing. you know, the ability for some countries to pursue these options and pursue foreign aid and pursue military interventions can be taken to by minority governments, coalition governments, caveats that are in place because the constitution. so it's a very complex decision-making process for governments and leaders to go through. its three dimensional checks in trying to decide what is best for the country, best for the people you represent. the good guys and bad guys sometimes change teams, which changes their entire outlook. and i still think coming back to

9:29 am

the pursuit of democracy as an implicit good is founded upon accountability, and people's ability to change their government, change the government when it makes atrocious decisions or exhibits of aggression against its people. and i guess that is the essential ingredient of democracy. i think that we admire most along with all the other goods -- there are lots of flawed democracies that you can point to, but i think people seen the control that they can have over their own government is why pursuing democracy is a worthwhile pursuit. >> and i just say, the road is very rocky. best example of course is eastern europe after the iron curtain fell. two steps forward, one step back. two steps forward, one step back. it's great difficult. it's very, very difficult, and we should never under estimate. it was hard for the east

9:30 am

european countries but you can imagine how difficult it is for some of the other parts of the world. >> we have a question up here. >> john, for senator mccain. would you be so kind, senator, to rate or evaluate american credibility military and diplomatic, in relation or as it is seen by russia and china, in terms of russia and china, i'm thinking of their conduct in the united nations security council. minister mackay was referring to that. and to the statement by hillary clinton that their behavior was despicable, yet nothing, nothing has occurred. arms shipping, russia support to a reprehensible person like assad, et cetera.

9:31 am

particularly in terms of iran, because american inaction on syria has obvious impact. but what america has said in terms of an engagement, red lines come is that there are red lines in relation to suspicious sites that might contain chemical weapons in iran, but there are no -- excuse me, in syria. but there are no red lines or no official red lines in relation to iran that is in pursuit of a nuclear weapon. and third, russia in general in its increasingly brazen, increasingly aggressively anti-american line, -- in the state duma. this brings in the whole issue of where democracy draw the li line. but mr. obama, if you recall the speech, i'm talking about moral

9:32 am

equivalency here, said that the cold war was stupid and useless, and had no positive outcome. america and russia were equal to win, after all, this was america's and its allies greatest triumph since world war ii. please rate america's credibility military and diplomatic in relation to those three countries, senator. >> another leading question. >> i don't, i don't like to be overly critical of my own government. i congratulate president obama on his reelection. of the and american people have spoken, and it's up to us as a little opposition to support the president whatever we possibly

9:33 am

can, especially on national security, foreign policy issue. very briefly, russia clearly has failed. the ngos being thrown out, the new definition of treason law that was just passed a couple days ago and russia. i mean, the list is a long. by the way, we're about to pass the bill through the united states senate. just went to the house but it will be very interesting to see mr. putin's reaction to that. i believe that vladimir putin believes in the near abroad. we see him meddling in the ukraine, in the baltics. we could go on for a long time, that my judgment of our relations with russia is that we're going to have to have an evaluation of that. because i do not believe the reset -- i mean, doing away with a non-lugar bill which is clearly, which has got to do with -- nunn-lugar bill, is clearly in russia's interest.

9:34 am

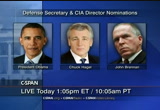

why in the world what they want him to get that? as far as iran is concerned, i think they're hurting very badly but i think there economy is in the tank. i think that got enormous difficulties, but yet we have not seen any deviation. in fact, there's a new iaea report showing that they have increased their centrifuge capacity. i believe one of the reasons is speed is just a couple minutes left in this program. see it in its entirety in the c-span video library. live now to the brookings institution for a discussion onn the potential affects of defense cuts from national security, including the possibility of lost jobs and decreased military readiness. this is live coverage on c-span2. >> just a quick note on the agenda, after bob have spoken, i will come up and call out a few folks, maybe we can ask some questions of bob. so that will be your chance to intercede and to pose questions that may be on your mind.

9:35 am

he will field questions for about half hour. at that point we'll go straight to a panel discussion moderated by peter singer, and we we joined by paul wolfowitz and richard betts. so again, thank you to all of you for being here. let me say a brief word about bob hale, for whom i have a great pleasure of working 20 years ago at the congressional budget office. fantastic career in national security. as noted, comptroller of the pentagon today. one of the top officials, the key adviser to the secretary of defense on all matters financial. not only in terms of building budgets but executing them and trying to figure out how to save money and execute efficiencies and reforms within the defense budget. bob has a long career in national security. he was a navy officer at the beginning of his career he worked at the center for naval analyses, work for the logistics management institute early in his career and again later. he was my boss at the

9:36 am

congressional budget office during the period, well, for a number of years, but including during the period when the berlin wall had just come down and rebuild a post-cold war military. working with people like senator sam nunn and aspen as most people on both sides of the aisle. bob was the comptroller of the air force during the clinton administration and has also been the executive director of the american society of military comptrollers. and so without further ado, please join me in welcoming one of my favorite budget experts, robert hale. [applause] >> well, good morning. how is everybody doing? good. listen, i'm glad to be here. for a number of reasons, but one of them is comptrollers don't get invited out that much. and is probably a good reason. i in a store, and then it was rushed to the hospital or doctors examined him and they said was that goodness and badness but the bad news is you that serious heart problems but if you don't get an transplant

9:37 am

you will die. he said but i've got, the good news is i've got three donors. you can choose any of them. one, a former 20 year old olympic athlete. she was practicing every day for the olympics to the second one was a 25 year-old warmer triathlete. he was biking and swimming everyday. the third one is an 80 or former dod comptroller. which one would you like? the man thought and said he will take i -- he said i will take the compost. and as wife was there and she said why would you choose an 80 year-old former comptroller for heart transplant donor but he said, i will take the one whose heart has never been used. [laughter] i will try my best. so the key issue facing us right now, how do we maintain national security and what are clearly under budget times. recently the main declines in defense budget have been in wartime. the overseas contingency process, but we have seen some

9:38 am

real declines in the base portion and there may be more coming. so what do we need to do to accommodate leaner times. i will offer three thoughts. starting with we need a strategy as to how we go about maintaining national security, but do it as reasonable. that's a first and maybe most important thing. second time we got to make more disciplined use of the money we get. we've got to stretch our defense dollars, and i'll tell you what we're trying to do. and third, we need i would suggest we need more stability both in terms of budget size and maybe particularly budget process. and i'll say a few words at the end about sequestration and other things that fall in that category. so let me talk about each of these points starting with strategy. it is the key to success at all times. and maybe particularly when you're facing lean budget times. you know that old sink him if you don't know where you're going, any road will be. i think without a strategy we would know where we're going.

9:39 am

we need -- you might say that's obvious but in some task of drawdowns there has been an across the board nature to them. i noticed the cold war drawdown after the cold war have some across the board aspects to it. so it's important that a year ago, january 2012, president obama announced a new defense strategy. we believe it is the right one for the times. and interestingly despite a lot of criticism for all of the specifics would propose in connection with a strategy, most members of congress seem to have accepted the strategy. it is meant to help us confront a period of time where we face a very complex national security challenges. i mean just think, security and arab spring to think iran and its relations with the whole world, include issue. think north korea and so many more. so what are the elements of this stretch? i'm not going to spend a lot of time on it but just briefly it assumes we will be smaller,

9:40 am

having forces but they will be highly ready forces but one of the way they will be limited will assume that these forces -- of the sort we conducted in iraq. but we will look for ways to reversibility, as we understand that we often guess wrong about future threats. we feel we must, forces must be highly ready because there's a very much of a no notice category or quality to the sorts of threats to national security. the second major item in a strategy is to rebalance our forces or the asia pacific and the middle east. we have done the middle east pretty well. we're working toward rebalancing forward asia pacific, maintaining presence there, moving around some forces, fewer marines, more on guam. a rotational presence in

9:41 am

australia, some more ships in singapore. possibly a presence in the philippines. we will pay attention to long-term threats in the asia area, including china. we will maintain technological superiority, the third element of this strategy, and invest more in some high priority types of activities, cyber, special operations. but we recognize we're going to have to cut back on weapons programs in order to meet our budget constraints. we used this tragic divide budget decisions. from fiscal 12 to 17, 100,000 people out of the active duty, 90% of those in the ground forces which is consistent with the decision on long prolonged operations. we think this strategy is the right one for the times. we also believe that the current level of defense i'm a plan to

9:42 am

defense spending, is roughly consistent with that strategy. and so we hope congress will continue to support that level, or at least something close to it. but strategy isn't enough in lean budget times. strategy is not enough in lean budget times. we all went to the taxpayers to stretch defense dollars wherever we can and we had a a number of initiatives to do that. often referred to as efficiencies. i don't like the term because little of what we are doing is truly an efficiency as an economist would he find them, same output, less funds. more often what we are doing is eliminating lower priority programs where we think that makes sense in order to hold down spending. i prefer the phrase more disciplined use of resources. so what have we done to make more disciplined use of resources? two major packages in the last two budgets, one for about 150 billion over five years, the

9:43 am

last year about 60 billion. and some cuts before that as well. many involved in lower priority weapons programs, we terminated the future combat system in favor of the more focus ground combat vehicle. we have terminated -- satellite in favor of the ahs. and we've ended production of both the to 17 and f-22 aircraft. and in another initiative some of the others focus on organization and business process changes. first time ever we this is not a combatant command. we have sought strategic sourcing across the grouping our by to try to use our market power to try to get better price. we look at things like consolidate e-mail networks and other more efficient i.t. efforts. reduce the use of contract services where began. and some activity that review qualify as efficiencies, the air force for example, has but like

9:44 am

programming software on their transport aircraft that will help pilots cut fuel costs. wireless contracts and the simple stuff we all do in our homes. we're trying to do in a bigger scale. another major set of initiatives has aimed at slowing the growth of military compensation which has grown very shortly over the past decade. we have proposed and congress has agreed to some increases in fees for military retirees. which hadn't been increased for the health care which has been increased for more than a decade. we've gotten congress to agree to increase in pharmacy co-pays and causing people to make greater use of mail order and generics and saves us a lot of funds. ..

9:45 am

>> we are committed to achieving audibility financial -- we have a realistic plan to accomplish what is a very major task. statements will help us improve our business processes, it'll force us to do that. but most importantly in my mind, they'll help reassure the public that we're good stewards of their funds. and we're not done seeking to make disciplined use of resources. we still need to consolidate infrastructure using the bray -- brac technique. in looking at a restructuring of the military health system. i recognize there's more to do here and that we haven't

9:46 am

fundamentally changed some problems for the department of defense like growth in operating costs and acquisition costs. and, indeed, also growth in military compensation. but i think it is fair to say that we have had a fairly aggressive ever effort to hold down defense costs, and that will continue. the last step in my mind that's a key to managing in leaner times is more stability both in terms of budget size and budget process. sometime over the next couple of months, i hope, to help the department submit a fifth defense budget, fifth one during my tenure as comptroller. the first two featured increases in the top line. the third one, in february 2011, featured substantial top line reduction, and the last one featured a significant reduction, about $260 billion over a five-year period, 487 over ten years. and, of course, we may not be done. the american taxpayer relief act which was the bill congress passed on new year's day on the

9:47 am

fiscal cliff regulation must force further reductions, and there is the threat of sequestration. at the same time, i would argue that national security challenges have not gotten any less complex. and this lack of budgetary stability makes it very hard to plan and, i think, extremely hard to plan well. so i think the nation's security would be better served if the congress adopted and then stayed with a more stable budget plan. we've also not enjoyed much process stability during my tenure as comptroller. i have personally coordinated four shutdown drills, two of them i was sitting in my office at 8:00 at night not knowing at midnight whether we would shut down the department or not. fortunately, we didn't under either case. we've learned under six-month continuing resolution, we are under one right now. they really hog tie the department and its ability to manage, very difficult to manage. there's just a number of legal restrictions. we had a near brush with

9:48 am

sequestration last week averted for the moment at least, but the continued specter of sequestration is certainly out this. in more than three decades of working in and around the defense budget, i've never seen a period featuring any greater budgetary uncertainty the than we're looking at over the next few months and through march. it gives a whole new meaning to the term march madness, and i can't wait for it to be over. so what does the rest of fiscal year 2013 look like? i know that we face, we know that we face sequestration starting now on march 1, 2013. we're still working on the details, but the total sequestration for dod appears to be roughly $45 billion if it all went into effect, about 9% of our budget. that is less than the sequestration we faced before passage of the new year's day act. that could have been as much as 12%. but we also have two fewer months in which to accommodate

9:49 am

those changes. we also cannot rule out an extension of the continuing resolution throughout the rest of this year, and that would sharply reduce the operation and maintenance funds that we have available and that we need to maintain readiness, and think back to my statement earlier: readiness is one of our highest priorities. and to add to the problems, we believe we must protect funds for wartime operations. we can't leave the troops in afghanistan, we haven't short shoplift them, and that means even larger cuts in dollars available for readiness. so the bottom line, we face a confluence of some unfortunate events, a yearlong continuing resolution that is going to reduce funds available especially for readiness, the possibility of sequestration and this need to protect our oco or wartime operations budgets. all of these together could lead to some serious, adverse effects on dod readiness, even as we p

9:50 am

continue to face some complex security challenges. and i've not even mentioned the disruption that sequestration could cause, more than 2,500 dod investment programs or projects. so we face a lot ofen certainty. -- uncertainty. we find ourselves balancing a lot of costs and risks. i'm reminded of a story that i think captures this and put a little lighter note on a somber talk. story about a speaker who was giving a talk on cost and risk, and he asked somebody b from the audience to come up, and he said aye got three questions for you. he said the first question's this, imagine there's a 40-foot-long i beam right here in front of me on the floor. it's 6 inches high. i'll pay you $100 if you take a chance to walk across that i beam, i'll pay you $100 if you fall off. would you take the risk? man said, sure. this time same i beam is strung between two 40-story buildings.

9:51 am

i'll give you $100 if you walk across. he said, of course not, if i fall off, i'm going to die. same question, i have one of your three children in my hand. if you don't walk across that i beam, i'm going to throw them off the building. would you take the chance? this time the man thought a moment and said, which child have you got? [laughter] so sometimes as a defense manager i feel like i'm throwing children, my own children sometimes, off a building, and sometimes i realize they may be some of your children as well. let me sum up, and then i'll try to answer your questions. i believe there are three key stems that we neat -- steps that we need to take as we seek to accommodate leaner budget times. we need a strategy that accommodates spending. we need to stretch every defense dollar, and a number of things we're doing, we need to continue to do them. and finally, we need more stability both in terms of size of budget and budget process. the decisions that are made over

9:52 am

the next few years and months, i should say, will be critical to our national security. i think secretary panetta put it just right last week when he said, and i want to quote: every day the men and women of the department of defense put their lives on the line to protect us all here at home. those of us in washington have no greater responsibility than to give them what they need to succeed and to come home safely. my hope is that in the next two months all of us in the leadership of the nation and the congress can work together to provide that stability. our national security demands no less. with that i'll stop and be glad to try to answer your questions. [applause] >> stay here if you like. >> i'll just briefly remind you of of the ground rules. please, identify yourselves after waiting for a microphone to arrive, and then, please, limit yourselves, if possible, to one clear question.

9:53 am

start here, sir. >> tony capas, i with bloomberg. you said $45 billion if sequestration kicks in in march. it was up to 62 billion potentially had it kicked in last week. what's changed, and will modernization take a disproportionate amount of in the hit if it happens because of your own rates? >> well, tony, what's changed is that they changed the law which changed both what we call the joint she sequester, sequestration, the way today reduced that amount, and also a potential sequestration today changed the caps in ways that cut it back. we wouldn't have the authority under sequestration to choose between o&m and modernization because it's the same percentage in each budget account in the case of the operating dollars, in each line item in the case of

9:54 am

investment. so unless we can reprogram, we would be pretty limited to do that, i suspect. we wouldn't have that option. >> [inaudible] >> it was 62 billion, that was our best estimate for dod before, and now our best estimates, still rough -- these legal changes were quite complex, but it looks like about $45 billion for defense. >> sir, here in the fourth row. >> hi. yeah, you seem o to be quite upset with smaller budget. does that mean you're going to be upset with your likely new boss, chuck hagel, who argues for a smaller budget? thank you. [laughter] >> well, first off, i'm not sure what the president would announce today, and if i did know, i wouldn't scoop him on that. i'm smart enough not to do that. [laughter] and i think if it's senator hagel, we will work with him, and we will work with the american people. defense budgets are about risk.

9:55 am

you get a certain amount of money, you get a certain amount of risk. if the country decides they want to take some more risk, we can go with lower budgets. we'll need to work with whoever is the nominee today, and assuming that person is confirmed, to try to make those trade-offs. they're hard to do, but we'll find another way to do them. >> a hand in that same row? okay. further back all the way to the wall, please. >> [inaudible] broadcasting. on the pacific realignment defense bill -- [inaudible] money for guam and okinawa because there's no -- [inaudible] the department has submitted to congress, and the senate and house have been saying this for a couple of years, so what is taking you guys long to get the report out? >> well, i mean, there are a number of complex issues, political and operational, with regard to the move of the marines from okinawa to guam. and we have been working on it.

9:56 am

we think we have a plan. we haven't yet fully convinced the congress. but i believe we will make this work. it may be later than we'd hoped, but i think we will come up with a plan that they will buy, and we will achieve our goal which is to maintain our presence in the pacific area while also moving some of the marines off of okinawa. >> here in the second row, please. and then we'll go to the front row after that. >> thank you. kate brannon from politico. could you talk about what assumptions you're using to build the 2014 budget and how those might have changed over the last couple months or even the last week? thanks. >> well, basically, the strategy is the one we've already announced, and i summarized very briefly. i think many of you know it well. that has been the overall guiding principle. the, we were planning on the same top line numbers that were announced with the budget a year

9:57 am

ago, the outyear numbers, and i don't know whether those will change or not. it's a possibility that they will given the american taxpayer relief act, the new year's day legislation on the fiscal cliff. we just don't know that yet. so there may be some dollar changes tbd. but i think the strategy will stay the same, it will certainly try to adhere to it because, as i said, we think it is the right one for the times. >> here. >> thank you. i'm jeannie -- [inaudible] with voice of vietnamese-americans. with your current state of the heart, would you give us the priorities of -- [inaudible] and how would you help senator senator hagel to shire the same -- >> i'm not sure i understood that. >> the priorities of spending in the budget for 2013-2014. >> what was the first part, mike if. >> the first part of your

9:58 am

question we both missed. >> i just refer back to your story of the state of your current heart. >> [inaudible] >> the joke. >> sorry. >> and would you tell us who is your most-loved child? laugh and then in the priorities of what's first, second and third. and then do you think senator hagel will share your love the same way, and how do you convince him? >> i know you all want me to say something about senator hagel, and i'm not going to. [laughter] i may not have a heart, but i do have a head, and i'm not going to -- [laughter] so whatever is the case, whoever is the nominee and if they're confirmed, we will work with them. obviously, that nominee will have to get in place and be confirmed, and that person, whoever it is, will have to tell us what their priorities are. but as of now we've got one secretary of defense. i think his priorities are clear, and i would hope that the broad ones would stay in place with regard to the strategy that i mentioned earlier. i know that's kind of a

9:59 am

nonanswer, but that's the best i'm going to do. >> i'm going to intercede with a question myself and try to be more specific -- >> you can't mention hagel. >> i will not. [laughter] however, i will mention robert griffin iii. you'll notice the clock stopped at 4:42, i think that's when his knee was injured, and we will forever leave the clock at that -- [laughter] but my question is to follow to some extent up on tony's and the issue of the procurement budget and what will happen to it. my understanding, of course, is we all know there's some prior year defense budgets that continue to fund industry, and so that is sort of good news for industry. as previous year's budget authority that's working off some of that, so the uncertainty about this year's budget authority is mitigated. orderly, it's very hard for industry and for you to enter into any contracts at all with the continuing resolution and the specker of sequestration. how should we understand the hit the defense industry is taking right now in percentage terms? is there a 5%, a 10%, a 20% cut

10:00 am

in the kinds of spending and jobs that might otherwise be taking place right now? >> are well, i mean, it's so hard to define what the baseline is right now. if you go against the '13 budget, the actual, the continuing resolution, the total dollars in the thing are actually a little higher than the proposal in the '13 budget. we've been limited to the fiscal '12 spending level, so not much has happened yet. i will say in the to try to be helpful. if sequestration occurs, the percentages have to be the same literally by line item. we won't have much ability to make changes. but if we simply get a target for a top-line reduction, we will try to do it in a balanced manner. but i think there's a long history and good reason why early in a drawdown the cuts tend tock heavily on the investment -- to be heavily on the investment portion of the budget, because it takes us a while to make force-level decisions and gradually draw

10:01 am

down the size of our forces. so if we are allowed the authority to make choices, they'll probably be investment-heavy in the beginning with more reductions in the operating costs after a couple of years when we can make force changes. and by allowed, we have to not only have the authority to do it under law, but we've got to get the u.s. congress to agree. and as some of you know if you follow it, they have some misgivings about our force level reductions that we've already proposed, let alone any that might have to come in the future. so we've got our work cut out for us. >> paul. >> paul wolfowitz, aei. you mentioned that you had saved quite a bit of money by terminating the c-17 and f-22, but my sense is this was done at the same time that we had a stimulus bill of $787 billion in order to create so-called shovel-ready jobs. and my guesstimate is that canceling those two programs probably cost somewhere in the

10:02 am

neighborhood of 50,000 shovel-ready jobs. and two-part question, one, do you have any idea what the exact number is, but more importantly, number two, am i correct in understanding that dod got none of the stimulus money? meaning that while you're expected to take the same kinds of cuts as domestic programs when it comes to cuts, when it came to increases four years ago, you got none of them, or certainly nothing comparable? >> we actually -- first, i don't know the job impacts, and i would argue strongly that i wouldn't -- i would prefer job effects not enter into decisions about what we do in defense. i think we ought to try to propose and implement a good strategy for the nation, and the job issue should be handled. they're very important, but it should be handled separately. we did get some of the stimulus money. we got, if memory's serving right, about $7 billion. most of it was -- seven, i believe. >> [inaudible] >> no. well, yes, it was about 1%.

10:03 am

but it was 7 billion. most of it in facilities sustainment and modernization on the bases, some military construction, those were the two major categories. personnel-related money. so we got some, not a huge amount. but seven billion is seven billion. so we participated, i guess, in job creation there. but as i said before, i understand how important jobs are in an economy that we are experiencing today, but i still believe the department's main job is to propose a national security strategy at a reasonable funding level that defends the nation, and the job issue should be handled by other means. >> let's look further back. go here in the fourth row, please. green sweater. >> hi, megyn scully with cq. just following up on the budget question for the fy-14 request. when do you expect that to be done, will it be delayed, and what are you doing right now to

10:04 am

try to game out the different scenarios? >> well, i think it's almost inevitable that there will be some delay, i just don't know what. normally, we would be transmitting data to omb right now, and we're not ready to do that. so i think some is inevitable, but it will be omb's call as to what delay occurs. i mean, we will, we will quickly start looking at alternatives as we do constantly in the programming process. i'm not going to go further than that, because i don't -- we don't have a lot of guidance yet, and i don't know exactly what those alternatives will be. but we will look at a variety in attempts to be as ready as we can when we get top-line guy dance. guidance. >> over here on the wall. take both these questions, please, and then move back. >> hi, i'm jen demaas owe with aviation week. i have a question. in august you and secretary carter testified to congress about some of the

10:05 am

sequestration's impacts, particularly i'm curious about the joint strike fighter that would involve cutting four of the platforms, and i'm wondering if that is still the case under sequestration now with a two month delay or or whether that changes the calculus at all. >> well, we were giving illustrations in august, and there will -- if sequestration goes into effect fully, which i hope it will not, incidentally, and i'm still, i've got my fingers crossed, and i'm hopeful it will not. but if it does, it would be a 9% reduction in each line item, roughly 9% in our budget, and that would include joint strike fighter production and separately it's r, d, t and e. the program managers are going to have to figure out exactly how they accommodate it, and i think there could be some reductions in unit buys, but i'm not prepared to say until they had a chance to do that what they would be for sure. >> sir. >> my name's jason gayle, i'm probably the only person in the room who's not a journalist. i represent industry. do you see besides low costs

10:06 am